Question from Valerie H.:

Is it true Yankee Stadium was built with special cement Edison himself had invented?

Continue reading “Invention Geek – Yankee Stadium and Thomas Edison?”

Question from Valerie H.:

Is it true Yankee Stadium was built with special cement Edison himself had invented?

Continue reading “Invention Geek – Yankee Stadium and Thomas Edison?”

Joseph Lister helped make surgery a much safer undertaking. Before Lister’s discovery, surgery was a last resort because of the high rate of post-operative infections. People believe that it was bad air in a hospital that caused infections after surgery. Preventative measures to prevent infections and diseases included airing out a hospital during the day.

Joseph Lister helped make surgery a much safer undertaking. Before Lister’s discovery, surgery was a last resort because of the high rate of post-operative infections. People believe that it was bad air in a hospital that caused infections after surgery. Preventative measures to prevent infections and diseases included airing out a hospital during the day.

Pasteur’s research which showed that the presence of micro-organisms caused rotting and fermentation was the basis for Lister’s research to make surgery safer. Pasteur suggested three ways to eliminate these organisms. One of these methods was exposure to chemical solutions.

Carbolic acid, a chemical which was used to deodorize sewage, was Lister’s chemical of choice. In August of 1865, Lister experimented with the chemical on the leg fracture of an eleven year old boy. He applied bandages dipped in carbolic acid to the leg wound. He removed the first bandages after four days and there was no sign of infection. After continuing to dress the wound with carbolic acid for six weeks, the boy’s leg healed perfectly with no signs of infection.

Continue reading “The Father of Modern Antisepsis”

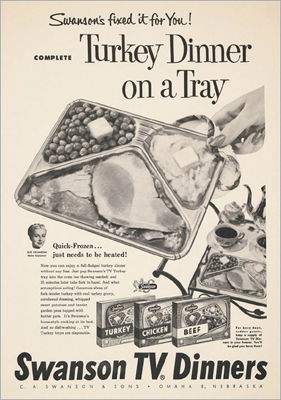

When Swanson introduced the TV dinner in 1954, it was an instant success. The frozen meal fit in perfectly with the nation’s obsession with prepackaged, convenience foods and a growing love of the television. At a price of 98 cents, the first meal sold was basically a Thanksgiving dinner with turkey, cornbread dressing, peas and sweet potatoes. Swanson hoped to sell about five thousand dinners the first year. Instead, sales hit more than 10 million.

When Swanson introduced the TV dinner in 1954, it was an instant success. The frozen meal fit in perfectly with the nation’s obsession with prepackaged, convenience foods and a growing love of the television. At a price of 98 cents, the first meal sold was basically a Thanksgiving dinner with turkey, cornbread dressing, peas and sweet potatoes. Swanson hoped to sell about five thousand dinners the first year. Instead, sales hit more than 10 million.

Although there were many frozen prepackaged meals before the Swanson’s TV dinner, none were as successful as Swanson’s in its aluminum three-compartment tray ready to be cooked at 425 °F for 25 minutes. Like many food inventions, the actual inventor of the Swanson’s TV Dinner is questionable. Gerry Thomas, an executive at Swanson, claimed he invented the frozen meal. But this claim has been disputed in recent years by other Swanson employees and Swanson family heirs. They claim the product was invented by the Swanson brothers, Clarke and Gilbert.

There are many accounts as to how Thomas formulated the idea for the TV dinner. In one story, the dinner was produced to use a large surplus of frozen turkeys which resulted from poor Thanksgiving sales. Another story is that inspiration for the meal came aboard a Pan Am Airways flight. The three-compartment aluminum tray was fashioned after the a tray in which a in-flight meal was served. Supposedly, the name for the meal did not come from the idea of eating the dinner in front of the television. Thomas designed the packing to resemble the front of a TV set with the inset screen and the rotary knobs. Continue reading “TV Dinner Controversy…”

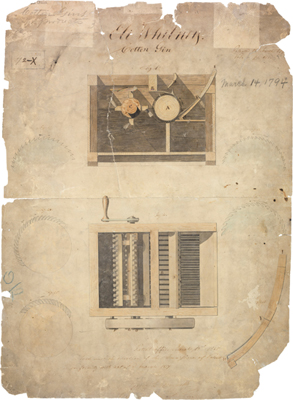

An invention can be so valuable as to be worthless to the inventor. Eli Whitney came to this conclusion because of the financial failure that was the cotton gin. Whitney gained fame and notoriety from his invention but did not gain the wealth he had anticipated.

An invention can be so valuable as to be worthless to the inventor. Eli Whitney came to this conclusion because of the financial failure that was the cotton gin. Whitney gained fame and notoriety from his invention but did not gain the wealth he had anticipated.

The cotton gin is a mechanical device that removes seeds from cotton. Before the invention of the gin, seeds had to be removed by hand. The cotton gin was a wooden cylinder with wire teeth. The teeth grabbed the cotton fibers and pushed them through a grate. The seeds were too large to fit through the grate so they were pulled away from the fibers. Whitney’s cotton gin could clean about 55 pounds of cotton a day.

The invention of the cotton gin changed the cotton industry in the United States. Whitney gave a one-hour demonstration of his new invention and farmers were ecstatic. They could now plant green seed cotton and remove the seeds much quicker and effectively.

Whitney did receive a patent for his cotton gin on March 14, 1794. This patent would later be numbered as X72. Whitney and his partner, Phineas Miller, did not actually intend to sell their product. They were planning to charge farmers for the service of cleaning the cotton. Their large price, two-fifths of a farmers profit, paid in cotton was the beginning of their financial problems.

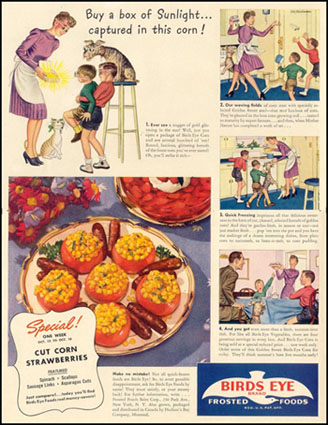

As a young adult, struggling to financially support himself through Amherst College by catching and selling frogs to the Bronx Zoo, Clarence Birdseye would later come into a great fortune within the food industry and be named ‘The Father of Frozen Food.’

As a young adult, struggling to financially support himself through Amherst College by catching and selling frogs to the Bronx Zoo, Clarence Birdseye would later come into a great fortune within the food industry and be named ‘The Father of Frozen Food.’

In 1912, Birdseye went on a fur-trading expedition to the Canadian province of Labrador when he realized that there was a fortune to be made in breeding and trapping foxes. He did just that for the next five years. He also did a fair amount of fur re-sale. Food supply in secluded parts of Labrador were little, so he ate things such as blackbirds, whale, lynx, lizards, starlings, alligator, beaver tail and skunk.

Birdseye was taught how to ice fish under thick ice by the native Inuit people. Once caught, he realized the fish froze almost instantly and when thawed, tasted fresh. Birdseye saw the preservative effects of extremely cold temperatures on fresh fish. He realized that this ‘fast freezing’ method could develop into a great way for people to have access to fresh food all year-round. Continue reading “The Father of Frozen Food”

Question from Felix:

Hey Invention Geek,

Is there a patent for the MRI machine? If so, who holds the patent?

Thanks for your question, Felix!

The short answer is: yes, there are, in fact, a few of patents associated with the development of the modern MRI.

The slightly longer answer includes stories of betrayal, intrigue, and full page ads in the New York Times.

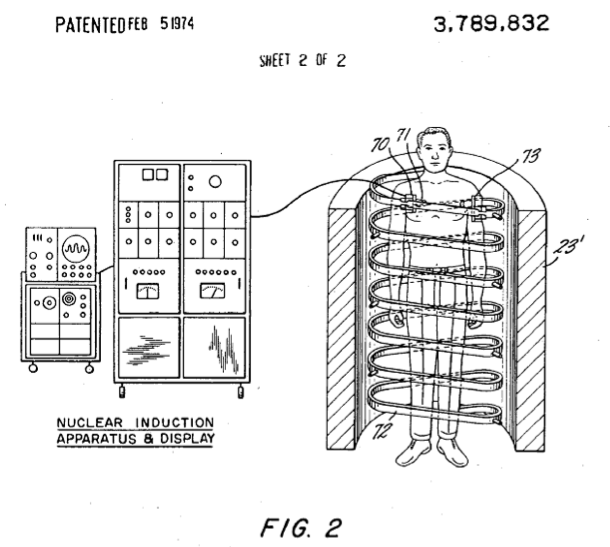

First of all, Raymond Damadian is widely credited with the initial discovery of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI).

After exposing tissue samples to nuclear magnetic resonance, Damadian observed a difference between tissue in a cancerous tumor and healthy tissue. He published an article in 1971 in the journal, Science, about his findings. In collaboration with other doctors, the first MRI for a full body scan was built in 1977. Damadian named it the “Indomitable,” because of the seven years of complex work needed to finish the project.

He obtained US patent 3,789,832 for the MRI machine, called an “apparatus and method for detecting cancer in tissue,” in February of 1974 and was eventually inducted into the National Inventor’s Hall of Fame for this achievement in 1989.

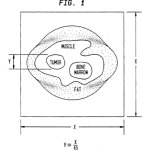

An image from Damadian's MRI Patent, issued Feb 5, 1974.

Now, while credit for the original MRI scanning machine goes to Dr. Damadian, credit for the development and refinement of magnetic imaging — which is what helps the machine do what it does as well as it does it — belongs mainly to chemist Dr. Paul Lauterbur. Damadian’s original patent had included the use of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) for diagnostic imaging, as it ahd been discovered a few decades earlier, but it turned out to be fairly inaccurate and was deemed unsuitable for diagnostic purposes.

Lauterbur's 1992 patent on NMR magnetic imaging.

Lauterbur’s work developing the use of NMR for magnetic imaging was crucial in the ultimate success of the MRI Machine as a diagnostic tool. The doctor worked for decades to improve the accuracy and reliability of the imaging process. In 1992, he was awarded patent 5081992 for a “method for calculating localized magnetic resonance spectra.”

In 2003, Dr. Lauterbur and British chemist Peter Mansfield were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for their work in the field.

But Dr. Damadian was not to be forgotten. After Lauterbur was awarded the Nobel prize in 2003, Damadian (or friends, as some stories have it) took out full page ads in the most popular newsparers denouncing Lauterbur’s win and demanding reconsideration. While there is no appeals or recall process for a Nobel Prize, Damadian did receive additional recognition in 2004 when he was awarded a Bower Award for scientific excellence by the Franklin Institute.

Dr. Lauterbur was finally given a well-earned place in the National Inventor’s Hall of Fame in 2007.

Both men contributed greatly to the advancement of modern medical diagnostic technology as we know it.

Ask away! If we choose to publish your answer online, you’ll get a free patent mug. Submit your question now!

Question from Douglas:

I use a ballpoint pen nearly everyday, who invented it?

Douglas,

The first ballpoint pen patent, 392,046, was issued to John Loud on October 30, 1888. Loud was a leather tanner and needed a writing device to assist him with marking leather and cloth. Regular fountain pens were unable to perform the tasks Loud needed. The new ballpoint pen worked well on tough surfaces, but was too rough for use of paper. The pen was never commercially produced.

View Loud’s patent here.

Irritated with how often he had to fill his fountain pen with ink, László Bíró, wanted to invent a better writing product. Bíró realized the ink used for newspaper printing dried quickly without smudging. He wanted to create a writing device that would dispense ink with the same qualities as the newspaper ink. László and Georg Bíró created the first commercial ballpoint pen. The brothers filed for a British patent on June 15, 1938. They also filed and received US patent 2,400,679 on May 21, 1946. The pen had a few kinks. However, thanks to a creative marketing strategy, the ballpoint pens were popular, especially among the British Royal Air Force.

View Bíró’s patent here.

Question from Archie:

The Wienermobile. What’s the deal with the vehicle? Does it have a patent?

What a great question, Archie!

Indeed, the “deal” with the Wienermobile is quite an interesting one, and, yes, it does have a patent associated with it.

It all started in 1936 when Karl Mayer, nephew to beloved meat magnate Oscar Mayer, imagined what would become the best known promotional vehicle (literally!) in American history.

Mayer chose the General Body Company of Chicago to realize this vision. The 13 foot long frank first rolled off the assembly line July 18, 1936 at a cost of $5,000 — no small price in the middle of the Great Depression!

The Original Oscar Mayer Wienermobile, 1936

While it spent the first few years of its life bound to the streets of Chicago, Wienermobile-mania continued to spread as the company began visiting towns across the country. Gas rationing in WWII may have kept the friendly frank off the streets for a time, but by 1969, the famed Wienermobile made its first trans-continental journey.

To protect his creation, Carl G. Mayer received a design patent D171,550 for an automotive vehicle on September 27, 1952. Any one of the fleet of 8 wandering wurst can now be seen across the United States, and even in foreign countries like Canada, Spain, or Japan.

In addition to the design patent, the Wienermobile is protected by a number of trademarks.

– TG

That’s right, if your question is chosen to be featured in our weekly “Invention Geek” column, we’ll send you a free one-of-a-kind patent mug custom pressed with a picture from your invention and the title of Honorary Invention Geek.

Got a pressing question about innovation history? Jump over to Ask the Invention Geek for details & an easy entry form!

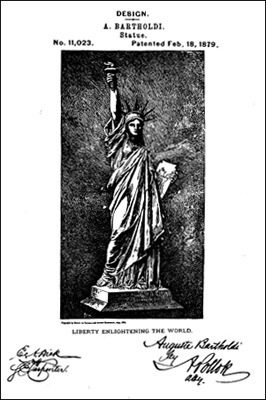

Did you know the subject of America’s most famous design patent wasn’t actually designed by an American?

Did you know the subject of America’s most famous design patent wasn’t actually designed by an American?

On February 18, 1879, French sculptor Auguste Bartholdi received US Patent D11,023 for a statue design – one he called, “Liberty Enlightening The World.”

You know her as The Statue of Liberty. She stands tall on her pedestal on Liberty Island, a beacon of hope for Freedom seekers the world over.

But, did you know the greatest symbol of American Opportunity almost didn’t happen due to a lack of funding? It’s true!

Auguste Bartholdi was commissioned in 1876 – the year of the American Centennial – to create the statue as a gift to America; it would be a symbol of friendship between France & the US for everyone to see. France would raise the money to build the sculpture, and America would handle the pedestal.

Simple, right?

Not really.

Even with Bartholdi’s patent – which he got specifically to allow him to create and sell replicas of Lady Liberty as a fundraising effort – France still had trouble finding enough public support. It took numerous auctions, art exhibits, lotteries and theater events were used to raise the needed funds from their end.

Construction of the statue began in 1875 and was not completed until nine years later in 1884. Alexandre Gustave Eiffel, the designer of the Eiffel tower, planned the skeletal framework for the statue. A larger-than-life representation of the Roman Goddess Libertas, Bartholdoi used two different women as models. The face is said to be a likeness of his mother. His wife posed for the arms and torso of Lady Liberty.

Meanwhile, America was having her own bit of funding problems. That is, until Joseph Pulitzer’s shame campaign against the wealthy and middle class alike spurred enough interest to finally fund the pedestal in 1885, just months before the statue – which had been shipped from France July of 1884 – arrived in New York.

So finally, on June 19, 1885, the world’s single, most powerful symbol of Freedom arrived in America in 350 pieces packed into 214 crates. They were reassembled in their place on Bedloe’s Island in New York Harbor. On October 28, 1886, before thousands of spectators, President Cleveland dedicated the Statue of Liberty on the now-named Liberty Island.

Lady Liberty stands 305 feet and 1 inch tall from its base to the tip of the torch and weighs 450,000 pounds. Each year over 3 million people visit the statue that has welcomed immigrants to Ellis Island since 1892.

Question from No Name:

When was the bulletproof vest invented? Or should I say Kevlar?

Kevlar was another accidental invention among many others throughout history that has saved thousands of lives. The fabric was originally intended to replace steel belting in the tires of vehicles. A member of DuPont’s Pioneering Research Laboratory, Stephanie Kwolek, first developed the synthetic material in 1965. Kwolek was awarded patent number 3,819,587 in 1974 for “Wholly aromatic carbocyclic polycarbonate fiber having orientation angle of less than about 45º.”

Kwolek had been hard at work developing new polymer solutions when she stumbled onto one that behaved in a way no other solution had before. The particular liquid separated into two distinct layers: one was clear and yellow, and the other was cloudy, shiny, and much thinner than other mixtures. It poured like water, which was also uncharacteristic.

Kwolek and technician Charles Smullen tested the liquid further, spinning it to fibers and ultimately discovering the material’s remarkable capabilities. The substance was lightweight, stronger than steel, chemical, flame, and high cut resistant.

Under DuPont, Kwolek’s material underwent testing as a bullet resistant fiber. DuPont first began marketing Kevlar in 1971 as bulletproof, protective body armor.

Today, Kevlar is used in many other products, including helmets, spacecraft shells, skis, and suspension bridge cables.

…all thanks to another “Happy Accident.”

_TG