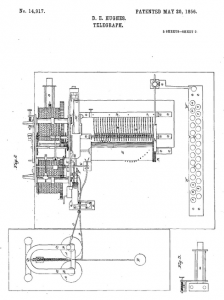

Hughes' US Patent 14,917 for a Telegraph Machine

It’s time to wish “Happy Birthday” to another inventor time sometimes seems to have forgotten, although it probably shouldn’t have.

You see, without music professor and serial tinkerer David Edward Hughes, a lot of modern conveniences – tv, radio, telephone, and music recording namely – probably wouldn’t exist. Although he was awarded countless honors in his lifetime, it seems he’s hardly a household name today.

Then again, as a man as well-known for his humility for his genius, maybe that’s how he’d have wanted it.

Born May 16, 1831, Hughes emigrated with his family from Wales to America when he was 7. The musically talented brood were known for their performances worldwide, and so it’s no surprise that David would go on to become a music professor at a Kentucky university.

But Hughes wasn’t happy simply teaching music. He often found himself combining the field with his deep interest in electrical engineering – and stumbled onto more than a few innovations as a result:

First, he invented a revolutionary telegraph printer in 1855 although that wasn’t his intent. Now known as the Hughes Printer, it was initially designed with piano keys to allow the man to copy & transmit musical notes over wire. A printer would then print out the letters of each note in sequence.

The then-infant Western Union Telegraph Company later adapted this system – piano keys and all – to allow letter telegraphy over the lines. It was a huge step up from the existing Morse Code systems.

Then, there was the first practical microphone, which Hughes first demonstrated in 1878. Originally invented some 50 years earlier by Charles Wheatstone and later ever-so-slightly improved by Alexander Graham Bell, it wasn’t until Hughes loosened an electrical contact inside the microphone’s circuitry that audio QUALITY really came to be.

Important as it was, Hughes chose to forgo a patent, instead giving the technology to the broadcast & recording industry outright. Many refer to this as the “birth of modern telephony” or “the birth of audio recording,” which would have hardly been possible with the pre-Hughes devices.

Inventor David Edward Hughes

But, it didn’t stop there. Hughes would go on to invent a number of important electrical devices, and introducing them with great humility. His spark-gap radio transmitter was the first to achieve a range of over 500 yards. His “coherer,” crystal detector, and induction balance (which is still used in certain metal detectors) were only some of the countless contributions he made to broadcast technology.

Despite the financial success and various accolades he received in his lifetime – including a Fellowship of the Royal Society, the Royal Society Gold Medal, and a Grand Gold Medal – Hughes was known for his unwavering modesty, deferring to the work of peers like Hertz and Marconi for their “more substantial” contributions.

After his death in 1900, The Royal Society of London created The Hughes Medal to recognize an “original discovery in the physical sciences, particularly as applied to the generation, storage and use of energy.” Today it is awarded in odd-numbered years. Past recipients include Stephen Hawking FRS and Alexander Graham Bell himself.