Did you know intellectual property protection in America is about as old as America itself?

Did you know intellectual property protection in America is about as old as America itself?

It’s true.

In 1787, the Constitution empowered Congress to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” Less than three years later, with the ink barely dry on the Patent Act of 1790, George Washington signed the very first patent ever issued in the United States.

While the patent system itself has evolved in many ways – now ornamental designs and even plants can be patented – the law remains conceptually unchanged since its inception.

Utility Patents: The Oldest of US Intellectual Property Protection

Administered By: USPTO (since 1836)

Available Since: 1790

Annual Applications: 482,871 (in 2009)

Total Patents Granted: over 8 million (since 1836)

Utility Patents are the oldest, most common patents in the United States. In 2010 alone, over seventeen times more utility patents were issued than all other types combined.

In order to be considered for a Utility Patent, the invention must, at the very least, be a machine, process, manufactured item, material composition – or an improvement on any of these. Known as the “Statutory Requirement,” this basic barometer of patentability is one of the broadest in the world. Additionally, the invention must also meet the following criteria:

- The invention must be distinct from abstract ideas or general laws of nature (ideas like this would be considered “non-statutory” and likewise “non-patentable”).

- The invention must be new and not have been sold, distributed, or publicly known in the US for over a year. Improvements on ideas considered common or known may themselves be patentable if they meet this and other requirements. (Novelty Requirement)

- The invention must be useful – ideas that don’t actually function as described are typically denied patents. Drawings and descriptions help fulfill this requirement today, but before 1880, applicants had to produce a working model of their idea to prove utility. (Usefulness Requirement)

- The invention must be non-obvious to someone skilled in the art. “Obvious” innovations may include a resizing of or new material for an existing object. Likewise, an application that seems to be simply a combination of other existing inventions without any unique improvement may also be considered “obvious” – and in either case unpatentable (Nonobviousness Requirement)

Technically speaking, the first utility patent was issued July 30, 1790 to Samuel Hopkins for the Making of Pot Ash. The patent was signed by George Washington himself. His was number X1 of over 9000 “X-Patents” issued by the original Patent Board under the authority of the Patent Act of 1790. Originally cataloged by date, it wasn’t until the recovery efforts after the Great Patent Fire of 1836 that these documents were serialized with the telltale “X” added before their number.

Technically speaking, the first utility patent was issued July 30, 1790 to Samuel Hopkins for the Making of Pot Ash. The patent was signed by George Washington himself. His was number X1 of over 9000 “X-Patents” issued by the original Patent Board under the authority of the Patent Act of 1790. Originally cataloged by date, it wasn’t until the recovery efforts after the Great Patent Fire of 1836 that these documents were serialized with the telltale “X” added before their number.

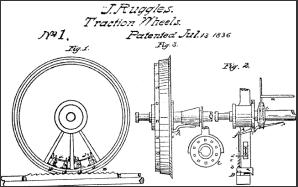

The Patent Law of 1836 marked the beginning of numeric serialization for all subsequent awards. Patent #1 under the new system was awarded to Senator John Ruggles of Maine for an improvement to locomotive engines. Ruggles was also instrumental in making the law itself.

As of 1995, Utility Patents are valid for 20 years from the application date, assuming any applicable maintenance fees have been paid.

Today’s patent law may seem more complex than the original Patent Act, but the spirit of offering protection for new and unique innovations remains intact.

In fact, it is that concept that carries over into all subsequent expansions of the Law including protection for ornamental designs of objects as well as protection for “invented” varieties of plants.