While it may never be known if the grass is ever really greener on or before any particular day in May, sand near the sea still sparkles from the light that would lead French engineer and physicist, Augustin-Jean Fresnel to study, then develop what is now known as the Fresnel lens. – which was not one lens, but numerous tiers of prisms.

Prism crystal glass that is.

Born on May 10, 1788, Augustin-Jean Fresnel was said to be a slow learner as a child however, Fresnel impressed his young friends by increasing the power of popguns and bows and for that they called him a genius.

But, “When applied to optics, his genius proved to be real and considerable. Where others had improved existing lighthouse technology, Fresnel leapt forward by studying the behavior of light itself. His studies both advanced the understanding of the nature of light and produced the most important breakthrough in lighthouse lights in 2,000 years.” – smithsonianmag.com

Also according to smithsonianmag.com:

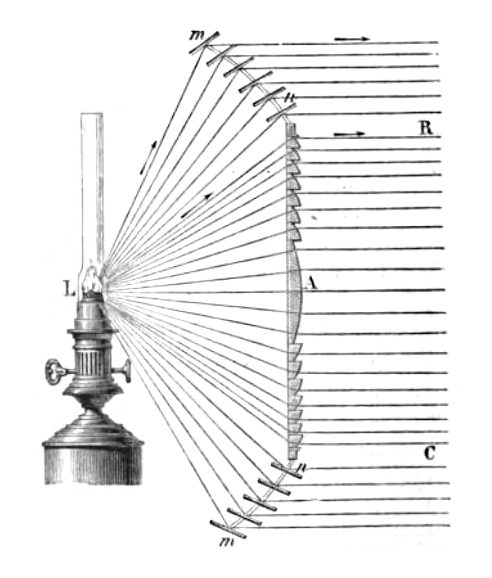

Fresnel worked out a number of formulas to calculate the way light changes direction, or refracts, while passing through glass prisms. Working with some of the most advanced glassmakers of the day, he produced a combination of prism shapes that together made up a lens. The Fresnel lighthouse lens used a large lamp at the focal plane as its light source. It also contained a central panel of magnifying glasses surrounded above and below by concentric rings of prisms and mirrors, all angled to gather light, intensify it and project it outward.

Soon, the sand by the sea that sparkled from the light that Fresnel studied became the barrier between the water and where the light went – as far as fifteen miles out to sea —by the lens that Fresnel invented, guiding thousands of ships safely into ports.

For many decades, the Fresnel lens was a fixture in lighthouses that were lit by whale oil, but, eventually the lenses would be replaced by rotating beacons and batteries — alleviating the need for a lighthouse keeper leaving the US Coast Guard to take over federally managing the waters and their lighthouses too.

Read how one state is bringing home the lens that belonged to the oldest operating lighthouse built in the early 1800’s: Georgetown lighthouse lens returning home

Augustin-Jean Fresnel died on July 14,1827 at the age of 39 but the legend of the lens he created has carried on.

The Theory of Fresnel Lenses – edmondoptics.com

The driving principle behind the conception of a Fresnel lens is that the direction of propagation of light does not change within a medium (unless scattered). Instead, light rays are only deviated at the surfaces of a medium. As a result, the bulk of the material in the center of a lens serves only to increase the amount of weight and absorption within the system.

To take advantage of this physical property, 18th-century physicists began experimenting with the creation of what is known today as a Fresnel lens. At that time, grooves were cut into a piece of glass in order to create annular rings of a curved profile. This curved profile, when extruded, formed a conventional, curved lens – either spherical or aspherical (Figure 2). Due to this similar optical property compared to a conventional optical lens, a Fresnel lens can offer slightly better focusing performance, depending upon the application. In addition, high groove density allows higher quality images, while low groove density yields better efficiency (as needed in light gathering applications). However, it is important to note that when high precision imaging is required, conventional singlet, doublet, or aspheric optical lenses are still best.

Fun Facts:

New applications have appeared in solar energy, where Fresnel lenses can concentrate sunlight (with a ratio of almost 500:1) onto solar cells.

It’s also been said the Fresnel lens can melt asphalt in seconds but, that’s probably not a good idea to try at home – or even in your own back yard.