Does this man look familiar? He should.

This week we celebrate one of the most important patents ever to cross a USPTO examiner’s desk.

The patent describes a process for a producing a material we use nearly everywhere – our homes, our cars, our offices, our hospitals – we even use it in space!

It’s one of the most abundant materials on the planet, and it is infinitely recyclable.

But, without the work of one brilliant young scientist, its full potential might never had been realized.

Do you know what it is?

It’s aluminum, of course!

Charles Martin Hall: Born to Do Great Things

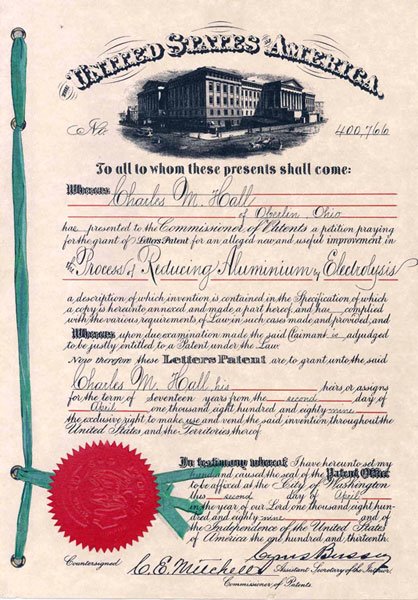

The original Patent Cover to Charles Martin Hall's Aluminum patent, issued April 3, 1889 - Image courtesy Alcoa, Inc

We’ve talked about child inventors before, but we’ve never covered anyone quite as prolific as Charles Martin Hall.

The fortunate son of a well-educated preacher, Charles Martin Hall was born in Oberlin, OH, in 1863. His mother began home schooling him early, and by six, he’d already found a passion in his father’s old Chemistry text book.

By twelve, Charles was spending every spare moment at home performing his own experiments. And by sixteen, he was enrolled in Oberlin College to study – you guessed it – Chemistry.

And it was here that one teacher – Yale-educated Professor Frank Fanning Jewitt – would inspire a real purpose in the young Hall.

Frank Fanning Jewitt: Be a Benefactor to the World

One day, Professor Jewitt shared a sample of aluminum with the class, proclaiming anyone who could invent a process to produce it on a commercial scale would “not only be a benefactor to the world, but would also [..] lay up for himself a great fortune.”

You see, aluminum does not typically occur alone in nature. And no one had yet figured out how to affordably extract it. So, it remained a precious metal reserved for jewelry and other “fancy” things. Hall took Jewitt’s challenge to heart and determined himself to be that benefactor.

Before Halls' discovery, aluminum was considered so precious it was chosen over gold & silver to become the cap on the Washington Monument! Image source: Library of Congress

Electrolysis: The Solution to AL Problems

Hall put countless hours into developing a better process for Aluminum extraction. When he graduated Oberlin College in 1885, he returned home to continue his work. Reviewing all his trials and failures so far, he decided on taking a new approach to the problem.

At home, Charles moved his lab from inside house to the summer kitchen (commonly called “the woodshed”) where he built himself a coal furnace and continued work on his experiments with the help of his dear friend and meticulous note-taking confidant, sister Julia Brainerd Hall.

Hall was determined to find a water-free liquid that would dissolve aluminum oxide via electrolysis (that is, using direct electric current to cause a chemical reaction).

And on February 10, 1886, after a nearly successful attempt led Hall to change the actual crucible he was performing his experiments in – he finally found success.

In that instant, Charles Martin Hall turned the most precious metal on the planet into something that would be afforded by anyone.

And, he was only 22 years old when he did it.

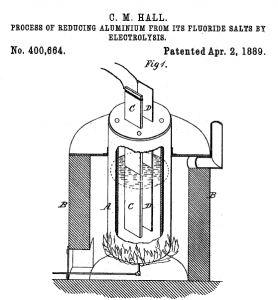

Hall filed for the patent only a few months later. And, on April 2, 1889, he was granted US Patent 400664 for a “Process of Reducing Aluminum from its Fluoride Salts By Electrolysis.”

An image of the aluminum production process, from Hall's US Patent 400664, issued April 3, 1889

Hall’s new process had reduced the production cost of aluminum by 99%, yet most potential financiers considered regarded his “revolutionary find” as nothing but a curiosity. That was until he connected with renowned metallurgist Alfred Hunt, who would go on to co-found the Pittsburgh Reduction Company with Hall in Pittsburgh, PA.

In 1907, the company – whose name was frequently confused with that of a similarly-named garbage collecting outfit – changed its name to The Aluminum Company of America.

Hall went on to fend off various patent challenges and even accusations of monopolization by the government, but he ultimately prevailed. He took a hands-on approach to running his company, continuing in research development and earning 22 patents before his sudden death at age 51.

Never married, the majority of Hall’s millions went back to Oberlin College and to support other educational endeavors around the world.

Aluminum: Here for the Long Haul

125 years later, Alcoa, Inc. remains the world’s third-largest producer of aluminum – to this day still employing the Hall-Héroult process, bearing the name of both Hall and the French chemist who independently (yet nearly simultaneously) discovered the same method.

No longer reserved for rich people’s jewelry and monumental adornments, aluminum is in everything from soda cans to prosthetic limbs to satellites.

It’s hard to imagine the stuff we use to wrap our leftovers was at one time considered more valuable than gold. But, it’s true.

Even more awesome is that aluminum it is nearly infinitely recyclable – via an even less costly process. Hall probably never considered that when he first started working with the metal, but it’s one of many incredible benefits resulting from his efforts.

So next time you do anything – take your lunch out of the fridge, watch your tv, drive your car – ANYTHING at all, consider thanking a small boy with a serious love for chemistry for making so much of what we have today possible.

More About Hall & The History of Aluminum:

Image Credits: Alcoa, Inc, The Library of Congress